Are We Really Teaching Tech?

A distinction got lost at the birth of STEM: it matters

It was the year 2000, and we were getting used to the internet fad, realizing it was probably here to stay. Among the newest, most exciting tech things were something called web logs, or, “blogs”, and all the cool kids had one.

Frustrated companies and organizations, trying to keep up with the new demand to supply everything and anything the public might want to know on their still-pretty-new websites, were starting to see the need for some kind of system to maintain what had only been dozens of pages a few years before, but now might run to thousands, even tens of thousands of pages.

(It was in 2001, that as their webmaster, I tried to get the managers of UNICEF Canada, to see why maybe we should try this new content management system idea out. I failed.)

And with the promise of bringing all the mounting chaos and ignored or unreachable information – now called “content” – into reach, a little outfit called Google had emerged, a couple of years before, and people were starting to use the name as a verb.

What we were experiencing then was the end of the web as a static, document-oriented system where HTML existed mostly to make pages look slightly less drab than default grey and Times Roman. Starting that same year, parents at Open Houses and Schools Fairs started to ask “What are you teaching in STEM?”. And this required a simple answer: basically, what they had been teaching for decades.

That question came up, because President Bush had just inaugurated the era of STEM, by associating the then-new acronym with a substantial funding bill that for the first time bound together all the component categories (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) as a kind of bellwether of the future of education.

Like other things Bush went on to say, like, “Iraq definitely has weapons of mass destruction”, there was a bit of imprecision in what he was talking about.

The outlier, the thing that needed an answer, was the Technology part. And it was obvious that the internet had to be part of the answer. All those weblogs and CMS’s and even Google itself were hugely influential in filling in the answer.

The thing was, weblogs, CMS’s and Google hadn’t been built out of HTML, and HTML alone wasn’t enough to answer, “What’s the T stand for?”. HTML was the Web, and the Web was supposed to be HTML, but HTML wasn’t the future.

This was the era when Web technology fused with coding. That’s what made all the newer-than-tomorrow services possible. And suddenly, it made sense to a lot of people that coding should be the star, the diva, of STEM’s Technology Extravaganza.

That’s why, when parents went on to ask, “and what about the Web? What are you teaching there?”, the answer was, “we have a wonderful new program teaching [fill in now-obsolete programming language of choice].”

We can wonder, then, why didn’t they use the acronym SWEM (w=web) or SIEM (I=internet) or SCEM (c=coding) or maybe SPEM (p=programming). And I think the answer comes right away; if your acronym doesn’t flow gently and easily from the lips, don’t bother. So STEM it was.

Technology became coding and coding became technology. And that’s where the imprecision comes from.

That was nearly a quarter-century ago. And not a lot has changed since. It might be time to review.

Language vs Technology

There’s a debate that never quite dies that goes, “is language a technology?”. There was a time when use of language was thought about much as the use of any tool is, and the answer was, “why, yes it is!”.

But then, in the 60’s through the 90’s, Noam Chomsky at MIT took time off from ending the Vietnam War, to ask, ‘How can it be the case that every human group (and no non-human groups, apparently), not only acquires language, but also uses language in ways that have strikingly similar structures such as verb/noun, and subject/object, and share the ability to construct infinite numbers of meaningful sentences, including never-before spoken sentences, that remain completely comprehensible to others in their language group?’

Chomsky’s early version of his theory got replaced; but (wouldn’t you know it?) by another Chomsky-originated idea. The new version doesn’t change much as far as the technology debate goes, though: language isn’t a technology if it’s effectively innate. That is, not needing to be created, or copied from an existing model, but rather always spontaneously arising in humans.

Contrast this with boat building; something that unquestionably is a technology, and a very ancient one. The fact is that practically every people that have lived near bodies of water (which of course, is almost all of us) make boats, which sets technology in that sense apart from the way language arises. Because it’s also true that desert people, and people who live in high country, on top of mountains and the like, don’t spontaneously invent boats. Even when the need for a boat is very small, the chances are good but not certain, boats will get made. But in the actual absence of need – no boats.

Talking to Machines

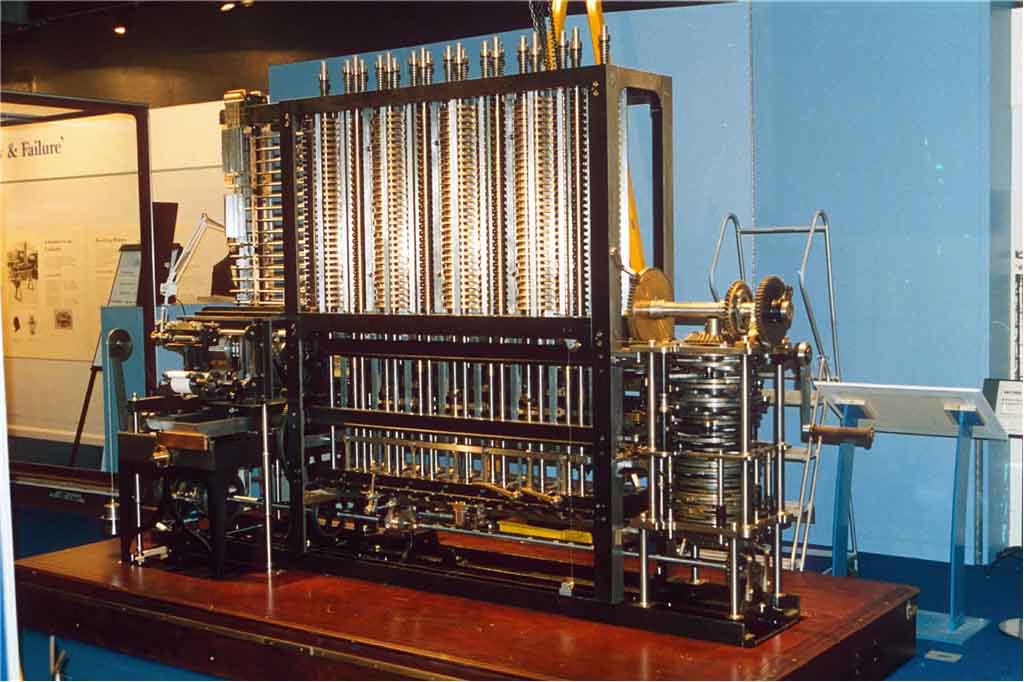

People started trying to figure out how to create machines that could compute things, when Victoria was on the throne, in the 1860’s. And right away, they saw the need to ‘talk’ to – i.e. program – the new creations that they were trying to build. It was a hard problem, and the incompleteness of early attempts was part of the reason that we don’t associate the Victorian Era with supercomputers.

Much later, at the dawn of the electronics age, the work of another Victorian, George Boole, was resurrected and supplied the bit (pun intended) missing from Victorian computer languages. That’s the part that now we call Boolean logic, and that’s the logical part of computers. But that logic still needed to combine with a way to ‘talk’ to machines; and so the origins of computer languages are inextricably bound to linguistics, as well as to logic.

So why does this matter? Well, if you see computer programming as the T in STEM, it doesn’t matter. It just means that teaching coding is what you’re doing, and technology is something else that simply made for a nicer acronym.

But if you look at the domains of technology that are part of our lives and careers, built into the world we live in, perhaps it’s worth thinking about it a bit more deeply. And to do that, we could return to boatbuilding.

It’s entirely legitimate to call boatbuilding a technology. That’s what it is; a planned process that uses tools to produce a means of changing the ways we live in the world fundamentally. With boat building, continents are no longer prisons, and wide rivers no longer barriers to other peoples and places.

It’s when you set out to actually build a boat that the technical depth (pun, once again, intended) of boatbuilding reveals itself.

Start with the basics: Every boat must have a surface that keeps water on one side and dry space on the other. If that stops working, the boat stops being a boat.

For thousands of years, boat building people have figured out ways to do this. One way was to cover the surface with skins, but this only served for boats up to a certain size. This has been made famous through the phrase, “I think we’re going to need a bigger bear”.

But in another boat-building techne, planks keep the water out; and that became a technology unto itself.

But this required that the spaces between the planks be filled with something – cotton, or oakum were and are common. So two technologies, both developed for making boats, and within the larger boatbuilding technology came to exist and work together, and bears were finally able to hibernate in peace.

But to what do the planks attach? Boats now needed ribs, ribs which embodied the essential form of the boat, that perfect shape that gives boats their beauty, and allows vessels to move as smoothly as possible through waves and flat water, encounter obstacles, and provide strength. This also became a subtle and involved technology, unto itself; but one that existed in a dynamic, give-and-take relationship to the planking process, much as those who caulk , or seal up a boat have give-and-take mutuality with those who plank the boat.

tl;dnr: Technology is about communication between disciplines.

And below the ribs, lies the keel, the strong spine that in its form determines many many aspects of the boat’s seaworthiness, its robustness, its capacity. The challenge of the keel-maker is that without an existing boat or anything to work from, they must take the determinative steps that limit and control, enable and restrict the boat in multiple ways, and with little chance of correcting later what has been done.

The ribs mate to the keel, and the same technological give and take that should be familiar already, is built in to the process of laying down the keel.

All of these technologies interact with each other, and there are dozens of other technologies that contribute to a finished Bluewater ready vessel. They all share tools in common, but also adapt or invent tools to specific needs. This sets the hammers used by those who caulk the hull, apart from the hammers that those planking the boat use to rivet the planks to the ribs. Both techniques comprise a shared understanding of what a hammer is, but make the hammer adapt to their needs.

Game Technology and Boat Building

It’s this complex dynamic that is both sequenced and interactive, and is embedded in boatbuilding, that we see in the game development process. And this is the reason why we use game development as the model for teaching technology in STEM.

This is also where the importance of distinguishing the linguistically-based coding that is so entrenched in STEM, from the technologically typical tasks and skills that go into our courses.

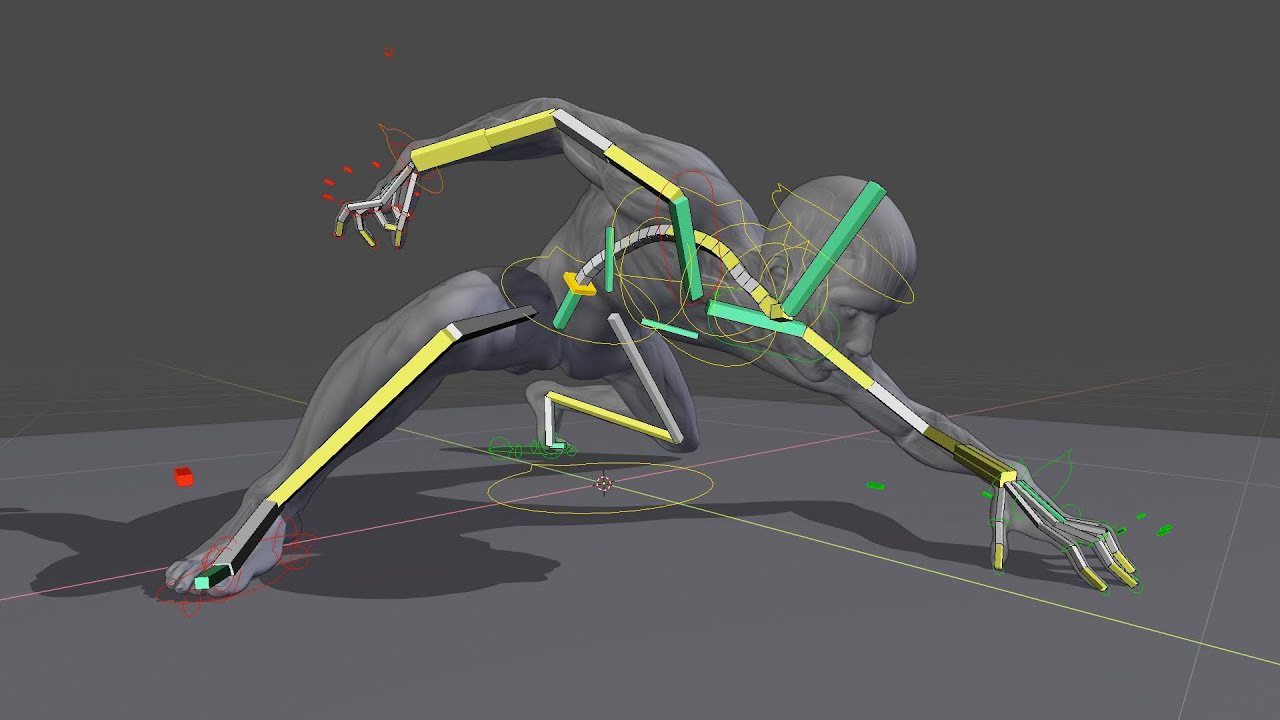

As ancient as boatbuilding is, it reflects exactly the modern dynamics of digital technical work. Distinct disciplines (keel, ribs, planking, caulking) are a model for the way an asset within a game – like a walking figure – is produced.

In our courses, a walking figure is a series of transformations, from a simple cube that is given a rough human form, to a stage where particular characteristics (age, gender, weight, caricature) are added to the refined figure. If you want to, you can see these as a parallel to the keel and rib stages.

To extend the analogy, articulation of the human form, by adding bones to it that allow motion to be controlled, followed by the manipulation of those bones over time to impart specific actions, exist in a less precise, but formally very similar relationship to the planking and the caulking; only at the last stage is the figure capable of moving through the world for which it is being created.

The key is that within the domain of coding, no analogous set of processes exists. And this means that while coding is a powerful skillset in a technologized world, it can’t teach our students much about the nature of a huge, growing, and well established domain of digital work – a domain that far more of them will have to master than will ever become software developers.

This comes down, I think, to the fact that coding isn’t a technology; as a key point of distinction, it doesn’t use tools, anymore than you need tools to use English or another natural language as your means of communicating with your language group.

Tools, which in the domain of game development include abstractions like data exchange standards, and best practices, are what make technology, technology. It’s those that align one operation – like sculpting a face – with the process of adding realistic (or fantastical) skin textures and nuances of colour. Both are necessary to the technologies of game development. Both entail communication skills, give and take.

In a world where the dynamics of interdependent digital disciplines are ubiquitous, and fundamental, the job of STEM is to impart and to enable these soft-skills for students. That is something that coding doesn’t do, as wonderful as it is.

If this article interests you, or raises questions, reach out to me, and let’s start a conversation about how your STEM program can adapt and expand, to bring the changes students deserve in STEM, to your school.